- Home

- Harry Paul Jeffers

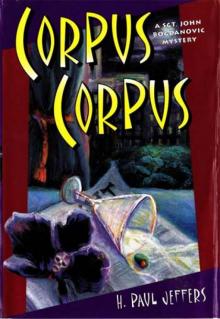

Corpus Corpus Page 12

Corpus Corpus Read online

Page 12

Swinging around in his chair, Bogdanovic faced a device that she supposed would have been welcomed by Archie Goodwin and viewed with suspicion by his employer, had the creator of Archie and his curmudgeonly employer lived longer.

Bogdanovic gleefully turned on the computer. "Let's have a gander at what the late Mr. Elwell's rap sheet can tell us."

Prompted by a few keystrokes and a decisive punching of the Enter button, the monitor screen flashed:

ACCESSING DATA. PLEASE STAND BY.

With a smile and wink at Dane, Bogdanovic said, "Good old data bank!"

A split second later as the screen provided the file Dane saw his expression turn to disbelief as the screen produced only a few lines of information.

"What the hell is going on here?" he demanded of the screen. "This is . . . it?"

Insistent fingers seemed to assault the keyboard, commanding the system to provide more, only to produce the same file.

"This can't be right," he said, angrily. "According to this, the son of a bitch had only one arrest. One charge of grand larceny in the second degree. He pleaded no contest."

"If it was grand larceny in the second degree," Dane said, thoughtfully, "it was theft of more than fifty thousand dollars, or larceny by extortion. The no contest smacks of plea bargain."

"Which suggests he was in it with somebody else," Bogdanovic said. "He cut a deal to testify against whoever that was. What's the normal sentence for larceny two?"

"It depends on the type of larceny. If it's embezzlement, for example, and it's a first offense, the judge would have wide discretion. He could even give probation with the stipulation of restitution. But that offense also covers, as I said, larceny by extortion. If the extortion was accompanied by the instilling of fear of physical harm, you're talking about serious prison time. But the criminal procedure law covering second-degree grand larceny also includes the use or abuse by a public servant of his official duties, such as failing or refusing to perform duties, thereby affecting some other person adversely."

"So what could Janus's interest have been in what looks to me like small potatoes?"

"It's small potatoes if Elwell was charged with a second-degree larceny. But I'd bet he wasn't. If he bargained to get off with second degree, he was probably looking at first degree."

"I'm listening, counselor."

"Grand larceny in the first degree involves property exceeding one million dollars."

"Therefore, if Elwell testified against someone charged with first degree, his testimony probably put whoever it was in prison for a lot more than five to ten. Such a person or persons might go a long way to take out revenge on Elwell, such as have him hit in the shower room."

"Why hadn't the revenge been taken sooner? Why now?"

"Because he was getting visits from a lawyer?"

"I think we may safely assume that Theo was not there in the role of Elwell's lawyer. Guys in prison don't refuse to see their lawyers. At the very least, they'd welcome an opportunity to get out of their cells. No, Theo was not representing Jake Elwell."

"Then who was he representing? The person or persons Elwell had testified against? Perhaps to try to persuade him to recant, thereby getting the case reopened?"

"That's possible. But in my conversation with Theo I had the impression that whatever he was pursing and regarded as potentially dangerous was not in the interest of a client. I may be wrong, but I can't help believing Theo was acting on his own."

"I could also be wrong about there being a link between the murder of Elwell and Janus's visit, but I don't think so," said Bogdanovic, pressing a button labeled Print Scrn. "Whether the chief of detectives agrees with me is another question. Come with me while I put it to him."

Looking startled to see them, Goldstein barked, "Are you two here to tell me you've cracked the case already?"

"It gets curiouser and curiouser," Bogdanovic answered as he placed the printout on Goldstein's desk.

Tilted back in his chair, Goldstein read it while fingers of his left hand twisted a few long strands of lank brown hair atop his balding head. "What could have been so important about a guy serving time for a five-year-old second-degree grand larceny that got Janus excited?"

"There are two ways of finding that out," Bogdanovic said. "We can ask ask the district attorney's office to root out the case file from the archives, which will probably take forever, or we get our hands on the files in Janus's law office."

Goldstein stopped the hair twisting and laid down the paper. "What is there to keep you from doing the latter?"

"Not a blessed thing, Chief," Bogdanovic said, smiling. "I'm just covering my ass."

"If you don't clear this case quickly and it turns into one more media threering circus with the mayor, police commissioner, and district attorney in the center ring, your ass will be in for a boot from my size-ten brogans whether it's covered or not. As to some lawyer in Janus's office giving you a problem in looking at the files, I'm sure I can rely on you to remind that person in your illimitable and charming manner that impeding the police in a murder in¬vestigation is a sure way to lose his law license."

"Excuse me, fellas," said Dane. "If Theo had a file on Jake Elwell it won't be found at his law offices. That's the sort of case he'd handle without involving his law firm. If a file exists, it's probably in his private files in the office at his ranch."

"That's where?" asked Goldstein.

"It's a few miles north of Larkville in Stone County. I've been there many times."

"That's good, because a certain Brooklyn born detective who shall go nameless grew up believing that spending an afternoon in the country was walking his dog in Prospect Park. With you along he won't end up getting his city boy butt lost in the woods and I won't have to call up my friend District Attorney Aaron Benson to send out a search and rescue party. Now, about getting entry to Janus's house. Is a member of his family likely to be there to let you in?"

"Theo had no family. A young man named Kolker lives on the ranch. He takes care of the horses and looks after the place when Theo is away. He knows me, so I'm sure he will cooperate."

"Good. I like people who cooperate with the police. More of them should do so. You two have a nice trip."

A FEW MOMENTS later as they waited in the sixteenth-floor lobby for an elevator, Bogdanovic said, "For the record, Maggie, that crack of Goldstein's about me getting lost in the woods is a bunch of baloney. Before that city boy he talked about became a cop he taught wilderness survival in the Marine Corps."

"Yes, sir. Duly noted, sir. Semper fi, SIR," she snapped.

As her hand jerked to her forehead, he looked at the curving fingers with the thumb tucked beneath with disgust. Scowling, he said, "That is the sorriest excuse for a salute I have ever seen. If you were in boot camp I'd order you to do two hundred push-ups in full pack."

"You can take the boy out of Brooklyn," she said as the door of the elevator slid open, "but you can never take the pride out of a marine. Theo was in the corps, you know."

"No I didn't," he said, pressing the button for the garage floor. "I figured him to be army. Judge Advocate General staff."

"He fought in Korea and got wounded in the retreat from the Chosin Reservoir."

"That was not a retreat. It was a strategic withdrawal."

"I'm sorry you never got to know the real Theodore Janus. He was so much more than the tough defense lawyer who gave you such a hard time as a witness, or the man who got under your skin at the Wolfe Pack dinner. He could be kind, generous, and caring. I'm sure that in his way he admired you. And I'm sure that wherever he is now, he's delighted that you are the one who will bring his murderer to justice."

When the elevator door opened to ranks of parked blue-and-white patrol units, police vans, and unmarked detective cars, Maggie smelled the acrid garage odor of countless drops of leaked motor oil and numberless years of automobile exhaust fumes. This was a world that was and always would be, she supposed, primarily a place for men

like the one striding beside her toward the plain black sedan that would convey them to the sun and fresh air of Theo Janus's ranch. No matter how many women were already in the ranks of the police, nor the number that might choose to follow them, as she hoped they would, this was a realm of hard men in steel vehicles. All sinew and muscle as hard as the rubber of the squealing tires that left black scars on the floor, they sprang into these modern chariots to speed away with their Glock pistols, as the knights of old in glinting armor carried broadswords in defense of a civilization that could not survive without them.

Gripping the steering wheel, the modern knight errant beside her was not one of the characters of detective fiction, certainly not Archie Goodwin on yet another mission for Nero Wolfe, but the real Sgt. John Bogdanovic of the New York Police Department with an actual murder case to be solved. That he had regarded the victim with little, if any, esteem was immaterial. Someone's life had been taken unlawfully and his solemnly sworn oath as a knight in a sports jacket and slacks was to see that the person or persons who committed that crime were brought to account.

As he drove out of the police department's garage, she saw him beginning a quest as sacred as any venture by a knight in the Middle Ages riding away on horseback toward the Holy Land to find the Holy Grail.

Aware of her eyes on him, he gave her a quizzical, sidelong glance and a quick, self-consciously boyish smile. "What is it?"

Embarrassed at being caught looking at him, she asked, "What is what?"

"Why were you looking at me like that?"

"Was I looking at you?"

"Yes."

"I'm sorry. I wasn't aware of it. I was just thinking. When I think about things, I look without seeing."

"What were you thinking about?"

"A man on a horse, actually."

'Janus? I've heard he was quite a horseman. Or was that one more part of the Janus mystique, like that cowboy hat, boots, and fringed buckskin jacket he always wore?"

"Oh dear," she gasped. "I wonder what will become of all his beloved horses? The last time I was at the ranch he had seven or eight of them. I've never seen such magnificent animals. Now, I suppose, they'll be sold when the estate is liquidated. How sad."

"Maybe he bequeathed them to someone in his will. This man Kolker, for instance." He smiled at her impishly. "Since you're a westerner, maybe he left them to you."

"No, the terms of the will provide that I get his all of his personal papers, the leather-bound collection of the opening and closing statements he delivered in his celebrated cases, plus all future royalties and subsidiary rights for his books."

"I don't mean to sound ghoulish, but does that mean you'll be as rich as Lily Rowan?"

"The potential for a lot of money is enormous. When he told me, I was flabbergasted."

"Did he happen to let you in on who else might stand to benefit from his death?"

"Enough to kill him for? You do have a policeman's mind! I'm glad I have an airtight alibi."

"You know what they say. Where there's a will—"

"For an ignoramus you have an amazing ability to inadvertently refer to a Nero Wolfe title. In this instance it's Where There's A Will At the Black Orchid dinner you gave me a glass of champagne and said—"

He smiled. "Champagne for one."

She fell silent a moment, thinking, then sighed deeply and declared, "Nero Wolfe was correct about wills. They are noxious things. It's astonishing the mischief they can provoke."

"I return to the question you have so skillfully avoided answering. Did Janus happen let you in on who else might stand to benefit from his death?"

"He did not, but I can try to satisfy your policeman's mind by reminding you that Theo had no family. His wife died a few years ago of cancer. They were childless. The bulk of his estate in the form of cash, stocks, bonds, and a valuable collection of Americana and American art will go to museums and colleges, as well as to the cancer society and several charities. I know all this because I worked with him on the conveyance instruments. Believe me, whatever residue there might be of Theo's estate would not be worth killing him for. In this case, where there's will there is no motive for murder."

"I had to ask. My job would be a lot simpler if the motive were good old greed. I'm a cop. I look for the obvious."

"If you read Nero Wolfe, you would know that nothing is obvious in itself. Obviousness is subjective. It was obvious to you that Theo was overbearing and arrogant. What was obvious to me about him was that he was—"

"I know. Generous, caring, loving, fighter for justice, and all-round good dude who loved horses. But somebody killed him."

THE CAR CRESTED a hill to reveal a shallow valley of gently undulating, snow-blanketed, sun-glistening pastures.

"In the summer," Dane said, "you'd see Theo's thoroughbred horses romping around or grazing in those fields."

"Very picturesque, I'm sure," Bogdanovic replied as the road became a long, curving descent toward a stretch of unleafed trees on both sides, their wall-like trunks and overarching limbs forming a tunnel. "How much farther?"

"The driveway is about a half a mile beyond the woods," Dane said as the car plunged into a darkness that enveloped them as totally as if someone had switched off a lamp. "You'll find white fencing with a gate on the left. The house is another mile or so up the driveway, tucked into a copse."

"Tucked into a cops?"

"C-o-p-s-e. A copse is a cluster of trees."

"Pardon me! I'm just a kid from Brooklyn where a tree was a tree, a bunch of trees was a forest, and cops—c-o-p-s—were guys with nightsticks who felt free to use them on your backside when you didn't move along after they told you to."

"There is more law at the end of a policeman's nightstick than in any ruling of the Supreme Court," she said, reciting as if she were a schoolgirl. "Thus endeth the reading of the gospel of law and order according to a nineteenth-century police captain by the name of Alexander 'Clubber' Williams."

"Well, old Clubber knew what he was talking about," Bogdanovic said as the tunnel ended, the light went on again, and a white slatted fence came into view.

Easing up on the accelerator, he slowed the car, wheeling it left between a pair of tall white poles supporting a curved wooden board into which had been burned:

LITTLE MISERY

Peering up at the sign as the car passed beneath, Bogdanovic said, "I'm afraid I don't get the point of the name."

"When Theo's namesake, Theodore Roosevelt, went west in the 1880s he settled in the Little Missouri area of the Dakotas. The people out there pronounced it 'Little Misery.' Theo adopted the name for his ranch because, he said, the name also summed up his mission as a defense attorney, which was to bring a litde misery into the lives of prosecutors and certain judges he considered to be pro-prosecution."

"Maybe we're on the wrong track. Maybe we should be taking a look at judges whose lives Janus made miserable."

"If you look to the bench for suspects, John, you'll have to investigate virtually the entire judiciary, including two sitting associate justices of the Supreme Court, as well as the criminal and civil courts of New York and several other states. Then there is His Honor Reginald Simmons, retired."

"What makes him stand out?"

"Theo handled the appeal of a case that Simmons regarded as his springboard to a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court. I'm sure you recall the case. A gang of long-in-the-tooth 1960s radicals suddenly surfaced in a botched robbery at a Stone County shopping mall."

"Hell yes I remember. They ambushed a van that was picking up cash from a branch bank. One of the guards was gunned down."

"Lawrence Newport was his name. The news media made him into a symbol of the times. The hardworking, middle-class family man with a loving wife, a two-year old son, and a baby on the way."

"The leader of the gang was a woman."

"Victoria Davis was the woman. She'd been on the FBI's most-wanted list for more than twenty years, ever since she ran away naked and screaming

after a radicals' bomb factory blew up on a quiet street in Greenwich Village."

"So how did Janus get involved?"

"Because of so-called inflammatory pretrial publicity, the trial was moved out of Stone County to Judge Simmons's courtroom in Queens. Davis was defended by the clown prince of all radical causes, Richard Hardon. As usual, he turned the proceedings into a carnival. As usual, he lost but claimed a moral victory. It was at that point that Davis's wealthy father asked Theo to handle an appeal. Because of his brilliant brief and his personal argument before the appeals court, which will be studied for years to come in law schools, the verdict was overturned by unanimous vote. Theo negotiated a deal that let Victoria walk out of jail with time served and probation. To make matters even worse, Simmons was excoriated for judicial errors. It was so humiliating, he had to retire from the bench and kiss his dream of a seat on the nation's highest court good-bye. I believe that's why Simmons, as a member of the steering committee of the Wolfe Pack, vehemently objected to giving Theo the Nero Wolfe Award. Frankly, I was surprised to see him at the dinner."

"That's all very interesting. It gives Simmons a motive, and his being at the dinner provided the opportunity. But what about means? Was Simmons one of those judges who pack guns under their black robes?"

"The only weapon Judge Simmons ever wielded was the blunt instrument known as a gavel."

As the car reached the house, a short, sinewy, suntanned black-haired young man in faded jeans, open shearling jacket, brown cowboy boots, and battered tan western hat ambled over to them from the direction of the stables.

"Good morning, Miss Dane," he said, tipping the hat as she and Bogdanovic left the car. "It's good to see you again."

"I'm sorry it's not a happier occasion."

Corpus Corpus

Corpus Corpus